The M1918A2 BAR

The Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) was a family of United States automatic rifles (or machine rifles) and light machine guns used by the United States and numerous other countries during the 20th century. The primary variant of the BAR series was the M1918, chambered for the .30-06 Springfield rifle cartridge and designed by John Browning in 1917 for the U.S. Expeditionary Corps in Europe as a rpelacement for the French-made Chauchat and M1909 Benet-Mercie machine guns.

The BAR was designed to be carried by advancing infantrymen, sling over the shoulder or fired from the hip, a concept called "walking fire"-thought to be necessary for the individual soldier during trench warfare. However in practice, it was most often used as a light machine gun and fired from a bipod (introduced in later models). A variant of the original 1918 BAR, the Colt Monitor Machine Rifle, remains the lightest production automatic gun to fire the .30-06 Springfield cartridge, though the limited capacity of its standard 20-round magazine tended to hamper its utility in that role.

History[]

John M. Browning, the inventor of the rifle, and Mr. Burton, the Winchester expert on rifles, discussing the finer points of the BAR at the Winchester plant.

The U.S entered World War I with an inadequately small and obsolete assortment of various domestic and foreign machine gun designs, due primarily to bureaucratic indecision and the lack of an established military doctrine for their employment. When the declaration of war on Imperial Germany was announced on Apr. 6, 1917, the military high command was made aware that to fight this machine gun-dominated trench war, they had on hand a mere 670 M1909 Benet-Mercies, 282 M1904 Maxims and 158 Colts, M1895. After much debate, it was finally agreed that a rapid rearmament with domestic weapons would be issued whatever the French and British had to offer. The arms donated by the French were often second-rate or surplus and chambered in 8mm Lebel, further complicating logistics as machine gunners and infantrymen were issued different types of ammunition.

Development[]

A live fire demonstration of the BAR in front of military and government officials.

In 1917, prior to America's entry to the war, John Browning personally brought to Washington, D.C. two types of automatic weapons for the purposes of demonstration: a water-cooled machine gun (later adopted as the M1917 Browning machine gun) and a shoulder fired automatic rifle known then as the Browning Machine Rifle or BMR, both chambered for the standard US .30-06 Springfield cartridge. Browning had arranged for a public demonstration of both weapons at a location in southern Washington D.C. known as Congress Heights.There, on Feb. 27, 1917, in front of a crowd of 300 people, Browning staged a love fire demonstration which so impressed the gathered crowd, that he was immediately awarded a contract for the weapon and it was hastily adopted into service (the water-cooled machinegun underwent further testing).

Additional tests were conducted for U.S. Army Ordnance officials at Springfield Armory in May 1917 and both weapons were unanimously recommended for immediate adoption. In order to avoid confusion with the belt-fed M1917 machinegun, the BAR came to be known as the M1918 or Rifle, Caliber .30, Automatic, Browning, M1918 according to official nomenclature. On July 16, 1917, 12,000 BARs wer ordered from Colt's Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company who had secured an exclusive concession to manufacture the BAR under Browning's patents. However, Colt was already producing at peak capacity and requested a delay in production while they expanded their manufacturing output with the new facility in Meriden, Connecticut. Due to the urgent need for the weapon, the request was denied and the Winchester Repeating Arms Company (WRAC) was designated as the prime contractor. Winchester gave valuable assistance in refining the BAR's final design, correcting the drawings in preparation for mass production.

Initial M1918 Production[]

2nd Lt. Val Browning with the BAR in France.

Since work on the gun did not begin until February 1918, so hurried was the schedule at Winchester to bring the BAR into full production that the first production batch of 1,800 guns was delivered out of spec; it was discovered that many components did not interchange between rifles and production was temporarily halted until manufacturing procedures were upgrated to bring the weapon up to specifications. The initial contract for Winchester called for 25,000 BARs. They were in full production by June 1918, delivering 4,000 guns, and starting in July were turning out 9,000 units a month.

By July 1918, the BAR had begun to arrive in France, and the first unit to receive them was the U.S. Army's 79th Infantry Division, which took them into action for the first time on Sept. 13, 1918. The weapon was personally demonstrated against the enemy by 2nd Lt. Val Allen Browning, the inventor's son. Despite being introduced very late in the war, the BAR made an impact disproportionate to its numbers; it was used extensively during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and made a significant impression on the Allies (France alone requested 15,000 automatic rifles to replace their notorously unreliable Chauchat machine rifle).

Design details and accessories[]

The M1918 is a selective fire, air-cooled automatic rifle using a gas-operated long-stroke piston rod actuated by propellant gases bled through a vent in the barrel. The bolt is locked by a rising bolt lock. The gun fires from an open bolt. The spring-powered cartridge casing extractor is contained in the bolt and a fixed ejector is installed in the trigger group. The BAR is striker fired (the bolt carrier serves as the striker) and uses a trigger mechanism with a fire selector lever that enables operating in either semi-automatic for fully automatic firing modes. The selector loever is located on the left side of the receiver and is simultaneously the manual safety (selector lever in the "S" position-the weapon is "safe", "F"-"Fire", "A"-"Automatic" fire). The "safe" setting blocks the trigger.

The weapon's barrel is screwed into the reciever and is not quickly detachable. The M1918 feeds using double-column 20-round box magazines, although 40-round magazines were also used in an anti-aircraft role; these were withdrawn from use in 1927. The M1918 has a cylindrical flash suppressor fitted to the muzzle end. The original BAR was equipped with a fixed wooden stock and closed-type adjustable iron sights, consisting of a forward post and a rear leaf sight with 100 to 1,500 yard range graduations.

As a heavy automatic rifle designed for support fire, the M1918 was not fitted with a bayonet mount and no bayonet was ever issued. Only one experimental bayonet fitting was ever made for the BAR by Winchester. This was a standard M1917 bayonet fitted at the Winchester factory with a special muzzle ring. The bayonet was attached to a standard M1918 BAR by means of a special experimental flash hider assembly. This prototype bayonet/flash hider assembly came from the Winchester in-house factory museum in New Haven, Connecticut with a tag printed on one side Winchester Repeating Arms Co./New Haven Conn., and handwritten on the other side: Combined Flash Hider, Front Sight and Bayonet Mount for Browning Automatic Rifle Model 1918 with Bayonet and Scabbard and the date-Sept. 7, 1918. There is no evidence whatsoever of military adoption nor a military stock number, name, or classification.

Variants and subsequent models[]

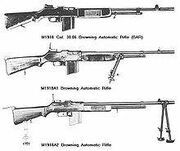

The primary U.S. M1918 variants.

The early M1918 BAR.

During its lengthy service life, the BAR underwent continuous development, receiving many improvements and modifications. The first major attempt at improving the M1918 resulted in the M1922 light machine gun, adopted by the United States Cavalry in 1922. The weapon used a new profile ribbed barrel, an adjustable spiked bipod (mounted to a swiveling collar on the barrel) with a rear, stock-mounted monopod, a side-mounted sling swivel and a new rear endplate, fixed to the stock retaining sleeve. The handguard was changed, and in 1926, the BAR's sights were redesigned to accomodate the heavy-bullet 172-grain M1 .30-06 ball ammunition then coming into service for machinegun use.

An FBI main practices with the Colt Monitor (R 80). The Monitor had a seperate pistol grip, and long, slotted Cutts recoil compensator.

In 1931, the Colt Arms Co. introduced the Colt Monitor Machine Rifle (R 80), intended primarily for use by prison guards and law enforcement agencies. Intended for use as a shoulder-fired automatic rifle, the Colt Monitor omitted the standard bipod, instead featuring a seperate pistol grip and buttstock attached to a lightweight receiver, along with a shortened 458 mm barrel fitted with a 4-inch Cutts compensator. Weighing 16lb 3 oz empty, the Colt Monitor had a rate of fire of approximately 500 rpm. Around 125 Colt Monitor automaic machine rifles were produced; of these ninety were purchased by the FBI. Eleven rifles went to the U.S. Treasury Department in 1934, while the rest went to various state prisons, banks, security companies, and accredited police departments. Although the Colt Monitor was available for export sale, no examples appear to have been exported to other countries.

In 1932, a greatly shortened version of the M1918 BAR designed for 'bush warfare' was developed by USMC Major H.L. Smith, and was the subject of an evaluative report by Capt. Merritt A. Edson, Ordnance officer at the Quartermaster's Depot in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. the barrel was shortened nine inches at the muzzle and the gas port and gas cylinder tube were relocated. The modified BAR weighed 13lbs 12oz and was only 34.5 inches long overall. Though it proved superior to the M1918 in accuracy when fired in automatic mode using the prone position, and equal in accuracy to the standard M1918 and ranges of 500-600 yards when fired from a rest, it was less accurate when fired from the shoulder, and had a lound report combined with a fierce muzzle blast, but this was more than offset by the increase in smoke and dust at the muzzle when fired, obscuring the operator's vision. Nor did it improve control of the weapon when fired in bursts of automatic fire. Though the report recommended building six of these short barrelled 'jungle' BARs for further evaluation, no further work was done on the project.

The M1918A1, featuring a lightweight spiked bipod, with a leg height adjustment feautre, attached to the gas cylinder and a hinged steel buttplate, was formally approved on June 24, 1937. The M1918A1 was intended to increase the weapon's effectiveness and controllability firing in bursts. Relatively few M1918s were rebuilt to the new M1918A1 standard.

M1918A2

In April 1938, work was commenced on an improved BAR for the U.S. Army. The latter specified a need for a BAR designed to serve in the role of a light machine gun for squad-level support fire. Early prototypes were fitted with barrel-mounted bipods, as well as pistol grip housings and a unique rate-of-fire reducer mechanism purchased from FN Herstal. The rate reducer mechanism performed well in trials, and the pistol grip housing enabled the operator to fire more comfortably from the prone position. However, in 1939, the Army declared that all modifications to the basic BAR be capable of being retrofitted to earlier M1918 guns with no loss of parts interchangeability. This effectively killed the FN-designed pistol grip and its proved rate reducer mechanism for the new M1918 replacement.

Final development of the M1918A2 was authorized on June 30, 1938. The FN-pistol grip and rate-reducer mechanism with two rates of automatic rife was shelved in favor of a rate-reducer mechanism designed by Springfield Armory, and housed in the buttstock. The Springfield Armory rate reducer also provided of automatic fire only, activated by engaging the selecor lever. Additionally, a skid-footed bipod was fitted to the muzzle end of the barrel, magazine guides were added to the front of the trigger guard, the handguard was shortened, a heat shield was added to help the cooling process, a small seperate stock rest (monopod) was included for attachment to the butt, and the weapon's role was changed to that of a squad light machine gun. The BAR's rear sight scales were also modified to accomodate the newly standard M2 Ball ammunition with its lighter, flat-base bullet. The M1918A2 walnut barrel-mounted carrying handle was added.

Because of budget limitations, initial M1918A2 production consisted of conversions of older M1918 BARs (remaining in surplus) along with a limited number of M1922s and M1918A1s. After the outbreak of war, attempts to ramp up new M1918A2 production were stymied by the discovery that the WWI tooling used to produce the M1918 was either worn out or incompatible with modern production machinery. New production was first undertaken at the New England Small Arms Company and International Business Machines Corp. In 1942, a shortage of black walnut for buttstocks and grips led to the development of a black plastic buttstock for the BAR. Composed of a mixture of Bakelite and Resinox, and impregnated with shredded fabric, the buttstocks were sandblasted to reduce glare. Firestone Rubber and Latex Products Company produced the platic buttstock for the U.S. Army, which was formally adopted on March 21, 1942.

Production rates greatly increased in 1943 after IBM introduced a method of casting BAR receivers from a new type of malleable pig iron developed by the Saginaw division of General Motors, called ArmaSteel. After successfully passing a series of tests at Springfield Armory, the Chief of Ordnance instructed other BAR receiver manufacturers to change over from steel to ArmaSteel castings for this part. During the Korean War, M1918A2 production was resumed, this time contracted to the Royal McBee Typewriter Co., which produced an additional 61,000 M1918A2s.

Contemporary models[]

In 2008, Ohio Ordnance Works introduced a modern, semi-automatic version of the Browning Automatic Rifle known as the 1918 A 3-SLR ("self-loading rifle").

The BAR in U.S. Military Service[]

World War I[]

At its inception, the M1918 was intended to be used as a shoulder-fired rifle capable of both semi-automatic and fully automatic fire. First issued in Sept. 1918 to the AEF, it was based on the concept of "walking fire", a French practice in use since 1916 for which the CSRG 1915 (Chauchat) had been used accompanying advancing squads of riflemen toward the enemy trenches, since the machine guns were too heavy to follow the troops during an assault.

In addition to shoulder-fired operation, BAR gunners were issued a belt with magazine pouches for the BAR and sidearm along with a "cup" to support the stock of the rifle when held at the hip. In theory, this allowed the soldier to lay supporessive fire while walking forward, keeping the enemy's head down, a practice known as "marching fire". The idea would resurface in the submachine gun and ultimately the assault rifle.

It is not knon if any of the belt-cup devices actually saw combat use. The BAR saw little action in WWI, in part due to the Armistice, and also because the U.S. Army was reluctant to have the BAR fall into enemy hands; the gun saw its first action in Sept. 1918. 85,000 BARs were built by the war's end.

Interwar use[]

During the interwar years, the BAR was standard issue to U.S. naval landing forces. The weapon was a standard item in U.S. ship armories, and each BAR was accompanied by a spare barrel. Large capital ships often had over 200 BARs aboard. Many of the U.S. Navy BARs remained in service well into the 1960s.

The BAR saw action with U.S. Marine Corps units participating in the Haitian and Nicaraguan interventions, as well as with the U.S. navy shipboard personnel in the course of patrol and gunboat duty along the Yangtze River in China. The First Marine Brigade stationed in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, noted that training a man to use the BAR proficiently took a full two days of range practice and instruction, compared to half a day with the .45 caliber Thompson submachine gun.

World War II[]

When the threat of new war arose, Ordnance belatedly realized it had no portable squad light machine gun, and attempted to convert the M1918 BAR to that role with the adoption of the M1918A2 by the U.S. Army on June 30, 1938. The BAR was issued as the sole automatic fire support for an eight-man squad, and all men were trained at the basic level how to operate and fire the weapon in case the designated operator(s) were killed or wounded. At the start of the war, most infantry companies designated two- or three-man BAR teams, a gunner and one or two assistant gunners (ammo bearers) who carried extra loaded magazines for the gun. By 1944, some units were using one-man BAR teams, with the other riflemen in the squad detailed to carry additional magazines and/or bandoliers of .30-06 ammunition. The average combat lifespan of a WWII BAR man was estimated to be 30 minutes. Despite various claims on the subject, the BAR was issued to soldiers of various heights.

As originally conceived, U.S. Army tactical doctrine called for one M1918A2 per squad, using either one or two men to support and carry ammunition for the gun. Fire and movement tactics centered around the M1 riflemen in the squad, while the BAR man was detailed to support the riflemen in the attack and provide mobility to the riflemen with a base of fire. This doctrine received a setback early in the war after U.S. ground forces encountered German troops well-armed with automatic weapons, including fast-firing, portable machine guns. In some cases, particularly in the attack, every fourth German infantrymen was equipped with an automatic weapon, either a submachine gun or full-power machine gun.

In an attempt to overcome the BAR's limited continuous fire capability, U.S. Army combat divisions increasingly began to specify two BAR fire teams per squad, following the practice of the U.S. Marine Corps. One team would typically provide covering fire until a magazine was empty, whereupon the second team would open fire, thus allowing the first team to reload. In the Pacific, the BAR was often employed at the point or tail of a patrol or infantry column, where its firepower could help break contact on a jungle trail in the envent of an ambush. A thirteen-man squad was developed, consisting of three four-man fire teams, with one BAR per fire team, or three BAR's per squad. Instead of supporting the M1 riflemen in the attack, Marine tactical doctrine was focused around the BAR, with riflemen supporting and protecting the BAR gunner.

Despite the improvements in the M1918A2, the BAR remained a difficult weapon to master with its open bolt and strong recoil spring, requireing additional range practice and training to hit targets accurately without flinching. As a squad light machine gun, the BAR's effectiveness was mixed, since its thin, non-quick-change barrel and small magazine capacity greatly limited its firepower in comparison to genuine light machine guns. The bipod and monopod, which contributed so much to the M1918A2's accuracy when firing prone on the rifle range, proved less valuable under actual combat conditions. The stock rest was dropped from production in 1942, while the M1918A2's bipod and flash hider were often discarded by individual soldiers and Marines to save weight and improve portability. With these modifications, the BAR effecively reverted to its origninal role as a portable, shoulder-fired automatic rifle.

During WWII, the BAR saw extensive service, both official and unofficial, with many branches of service. One of the BAR's most unusual uses was as a defensive aircraft weapon. In 1944, Captain Wally A. Gayda, of the USAAF Air Transport Command, reportedly used a BAR to return fire against a Japanese Army Nakajima fighter that had attacked his C-46 cargo plane over the Hump in Burma. Gayda shoved the rifle out his forward cabin window, emptying the magazine and apparenly killing the Japanese pilot.

Korean War[]

Korean War, 1951: Taking cover behind their escort tank, a U.S. soldier returns fire on Chinese positions with an M1918A2.

The BAR continued in service in the Korean War. The last military contract for the manufacture of the M1918A2 was awarded to the Royal Typewriter Co. of Hartford, Conn., which manufactured a total of 61,000 M1918A2s during the conflict, using ArmaSteel cast receivers and trigger housings. In his study of infantry weapons in Korea, historian S.L.A. Marshall interviewed hundereds of officers and men in after-action reports on the effectiveness of various U.S. small arms in the conflict. General Marshall's report noted that an overwhelming majorithy of respondents praised the BAR and the utility of automatic fire delivered by a lightweight, portable small arm in both day and night engagements.

A typical BAR gunner of the Korean War carried the twelve-magazine belt and combat suspenders, with three or four extra magazines in the pockets. Extra canteens, .45 pistol, grenades, and a flak vest added still more weight. As in WWII, many BAR gunners disposed of the heavy bipod and other accoutrements of the M1918A2, but unlike the prior conflict, the flash hider was retained because of its utility in night fighting.

The large amounts of ammunition expended by BAR teams in Korea placed additional demands on the assistant gunner to stay in close contact with the BAR at all times, particularly on patrols. While the BAR magazines themselves always seemed to be in short supply, Gen. Marshall reported that "riflemen in the squad were markedly willing to carry extra ammunition for the BAR man."

In combat, the M1918A2 frequently decided the outcome of frenzied attacks by North Korean and Chinese Communist forces. Communist tactical doctrine centered around the mortar and machine gun, with attacks designed to envelop and cut off United Nations forces from supply and reinforcement. Communist machine gun teams were the best-trained men in any given North Korean or Chinese infantry unit, skilled at placing their heavily camouflaged and protected weapons as close to UN forces as possible. Once concealed, they often surprised UN forces by opening fire at close ranges, covering any exposed ground with a hail of accurately sighted machinegun fire. Under these conditions, it was frequently impossible for U.S. machine gun crews to move up their Browning M1919A4 and M1919A6 machine guns in response without taking heavy casulaties; when they were able to do so, their position was carefully noted by the enemy, who would frequently kill the exposed gun crews with mortar or machine gun fire while they were still emplacing their guns. The BAR gunner, who could stealthily approach the enemy gun position alone (and on his stomach, if need be), proved invaluable in this type of combat.

During the height of combat, the BAR gunner was often used as the 'fire brigade' weapon, helping to bolster weak areas of the perimeter under heavy pressure by Communist forces. In the defense, it was often used to strengthen the frepower of a forward outpost. Another role for the BAR was to deter or eliminate sniper fire. In the absence of a trained sniper, the BAR proved more effective than the random response of five or six M1 riflemen.

Compared to WWII, U.S. infantry forces saw a huge increase in the number of night engagements. The added firepower of the BAR rifleman and his ability to redeploy to 'hot spots' around the unit perimeter proved indispensable in deterring night infiltration by skirmishers as well as repelling large-scale night infantry assaults.

While new-production M1918A2 guns were almost universally praised for faultless performance in combat, a number of malfuntions in combat were reported with armory-reconditioned M1918A2s, particularly weapons that had been reconditioned by Ordnance in Japan, which did no replace operation (recoil) springs as a requirement of the reconditioning program. Ordnance addressed the problem of maintaining the problematic gas piston by issuing disposable nylon gas valves. When the nylon valve became caked over with carbon, it could be discarded and replaced with a fresh unit, eliminating the tedious task of cleaning and polishing the valve with wire brush and G.I. solvent.

Vietnam War[]

The M1918A2 was used in the early stages of the Vietnam War, when the U.S. delivered quantities of 'obsolete' second-line arms to the South Vietnamese Army and associated allies, including the Montagnard hill tribespeople of South Vietnam. U.S. Special Forces advisors frequently chose the BAR over current infantry weapons. As one Special Forces sergeant declared, "Many times since my three tours of duty in Vietnam I have thanked God for ... having a BAR that actually worked as opposed to the jamming M16 ... We had a lot of Vietcong infiltrators in all our [Special Forces] camps, who would steal weapons every chance they got. Needless to say, the most popular weapon to steal was the venerable old BAR."

Post-Vietnam use[]

Quantities of the BAR remained in use by the Army National Guard up until the mid-1970s. Many nations in NATO and recipients of U.S. foreign aid adopted the BAR and used it into the 1990s.